Why Argument Structure Matters

Before we dig into the three types, let's talk about why this even matters.

You could have the best evidence in the world, but if you organize it poorly, your reader won't follow your logic. Think of argument structure like building architecture. You wouldn't put the roof on before the foundation. Same with arguments, you need to build them in an order that makes sense.

Here's what good structure does:

- Guides the reader through your logic step by step

- Makes counterarguments feel less threatening by addressing them strategically

- Emphasizes your strongest points by placing them where they'll have the most impact

- Prevents confusion by organizing complex ideas systematically

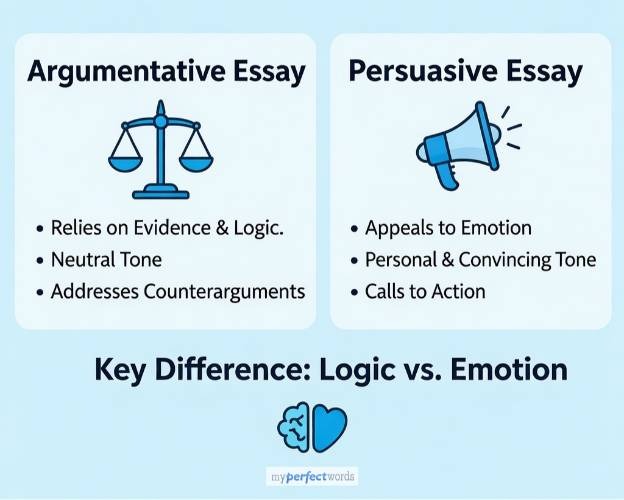

- Increases persuasiveness by matching structure to your audience's mindset but dont be so persuasive. To learn the difference check the argumentative essay vs persuasive essay guide.

The wrong structure can:

- Make your reader defensive from the start

- Bury your best evidence where it won't be noticed

- Confuse readers about what you're actually arguing

- Make counterarguments seem stronger than they are

So picking the right argument type isn't just academic theory. It's a strategy.

Need the complete writing process from start to finish? Check out our complete argumentative essay guide.

3 Main Types of Argument

There are 3 types of arguments that you'll most likely encounter while writing an argumentative essay. These are:

Classical Argument

This is the OG the original argument structure developed by Aristotle over 2,000 years ago. It's still the most common type you'll encounter because it's clear, direct, and effective.

| Definition: A Classical argument is a type of argument structure where you present your position clearly, support it with evidence, address counterarguments, and prove why your side is correct. |

How Classical Arguments Work

Classical arguments use three modes of persuasion (Aristotle called them appeals):

Ethos (Credibility):

- Establishing that you're trustworthy and knowledgeable

- Using credible sources

- Showing you've done your research

Pathos (Emotion):

- Appealing to the reader's values and feelings

- Using examples that resonate emotionally

- Making the reader care about the outcome

Logos (Logic):

- Presenting facts, statistics, and evidence

- Using logical reasoning

- Building a step by step case

| The key is balancing all three. Too much emotion, and you seem manipulative. Too much logic and you're boring. Too much credibility-building and you sound arrogant. |

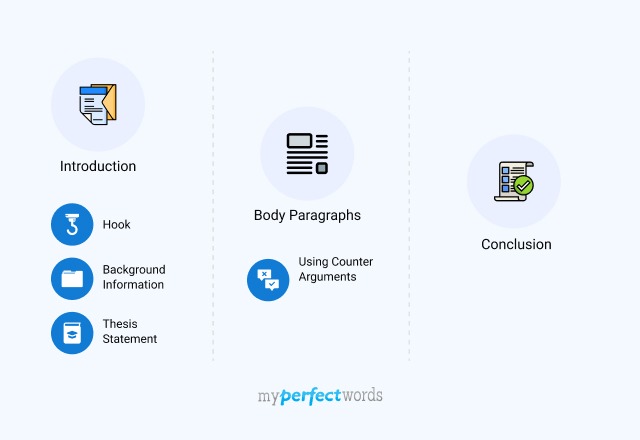

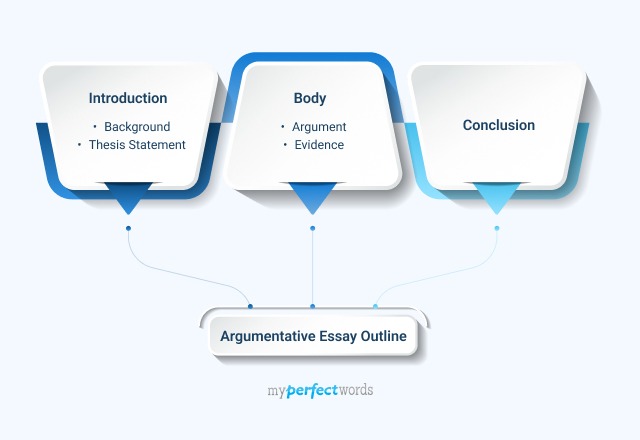

Classical Argument Structure

Here's the standard organization:

Introduction: hook, brief background, thesis statement

Narration (Background):

- Explanation of the issue

- Why it matters

- Context your reader needs

Confirmation (Your Arguments):

- Your main arguments with evidence

- Typically 3-5 strong points

- Each point gets its own section with supporting evidence

Refutation (Counterarguments):

- Acknowledge opposing views

- Address them directly with evidence

- Show why they don't hold up

Conclusion:

- Restate your position (in different words)

- Summarize why your side is correct

- Call to action or final compelling statement

When to Use Classical Arguments

Classical works best when:

- There's a clear right/wrong or yes/no answer

- Your audience is neutral or undecided

- You have strong evidence that definitively supports your side

- The topic isn't highly emotional or polarizing

- You want to win the argument, not find compromise

Don't use Classical when:

- The topic is extremely controversial (gun control, abortion)

- Your audience is hostile to your position

- There's no clear "right" answer

- You need to find middle ground rather than "win"

Example: Classical Argument in Action

Topic: Should college education be free? Thesis: Free public college tuition would benefit society by increasing social mobility, reducing student debt, and creating a more educated workforce. Structure: Intro: Statistics about student debt crisis + thesis Background: Current state of college costs Argument 1: Social mobility evidence Argument 2: Economic benefits of debt reduction Argument 3: Workforce education levels Counterargument: "But it's too expensive!" = Show how it could be funded Conclusion: Benefits outweigh costs |

Why this works: The topic has a clear position, there's substantial evidence available, and you can definitely argue one side is better than the other.

Want to see full essay examples using Classical structure? Check out our argumentative essay examples with analysis.

Toulmin Argument

Developed by philosopher Stephen Toulmin, this model breaks arguments down into their logical components. It's like showing your work in math class you prove your conclusion is valid by showing each step.

| Definition: A Toulmin argument is a type of argument structure that breaks claims down into six components: claim, grounds, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal. |

How Toulmin Arguments Work

Toulmin arguments are all about logical precision. Instead of just stating your claim and giving evidence, you explain the reasoning that connects your evidence to your claim. This makes your logic transparent and harder to attack.

The Six Components:

1. Claim: Your main argument or thesis. What you're trying to prove.

| Example: "The voting age should be lowered to 16." |

2. Grounds The evidence supporting your claim. Facts, statistics, examples.

| Example: "Research shows 16-year-olds have the civic knowledge and maturity to make informed voting decisions." |

3. Warrant The reasoning that connects your grounds to your claim. Why does that evidence support this conclusion?

| Example: "If 16-year-olds possess the necessary knowledge and maturity, they meet the requirements for voting rights." |

4. Backing Additional support for your warrant. Why should we accept your reasoning?

| Example: "Cognitive development research shows most people reach adult-level reasoning by age 16." |

5. Qualifier Limitations or conditions on your claim. Words like "usually," "probably," "in most cases."

| Example: "In most democratic societies, lowering the voting age would likely increase youth civic engagement." |

6. Rebuttal Acknowledgment of situations where your claim might not hold or counterarguments.

| Example: "However, in areas with extremely low educational quality, additional civic education might be needed first." |

Toulmin Argument Structure

Unlike Classical and Rogerian, Toulmin doesn't prescribe a specific essay structure. Instead, you can organize it however makes sense for your argument, as long as you include all six components.

Common organization:

Introduction: Present your claim clearly

Body Section 1: Grounds + Warrant

- Present your evidence

- Explain why it supports your claim

- Provide backing for your reasoning

Body Section 2: Additional Grounds + Warrants

- More evidence with explained reasoning

- Build a layered logical case

Body Section 3: Qualifiers + Rebuttal

- Acknowledge limitations

- Address counterarguments

- Show your claim still holds despite these

Conclusion

- Restate claim with qualifications

- Summarize the logical chain

When to Use Toulmin Arguments

Toulmin works best when:

- Your argument is complex with many moving parts

- You need to prove tight logical connections

- Your claim has legitimate limitations or exceptions

- You're writing for an academic audience

- The issue requires nuanced analysis

Don't use Toulmin when:

- Your argument is straightforward and doesn't need breakdown

- You're writing for a general audience (it can feel overly technical)

- The claim is simple and doesn't have qualifications

- Your priority is emotional persuasion over logical proof

Example: Toulmin Argument in Action

Topic: Should employers be allowed to require vaccination for workplace safety? Claim: Employers should be able to require COVID-19 vaccination for on-site workers. Grounds: Studies show vaccination significantly reduces workplace transmission and illness. Warrant: Employers have a legal responsibility to provide safe workplaces, and vaccination is a proven safety measure. Backing: OSHA regulations require employers to eliminate recognized hazards; COVID-19 is a recognized hazard, and vaccines are an available elimination method. Qualifier: This applies in most workplace settings, particularly those with in-person interaction. Rebuttal: In remote-only positions or jobs with no in-person contact, vaccination requirements may be excessive. Additionally, reasonable accommodations must be made for those who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons. |

Why this works: This topic has lots of nuance. It's not a simple yes/no it depends on the workplace, the role, and individual circumstances. Toulmin lets you make a strong claim while acknowledging its limitations.

Rogerian Argument

Named after psychologist Carl Rogers, this approach is completely different from Classical. Instead of trying to win, you're trying to find common ground.

| Definition: A Rogerian argument is a type of argument structure that seeks to find compromise and mutual understanding between opposing viewpoints rather than proving one side correct. |

How Rogerian Arguments Work

The Rogerian model is based on Rogers' therapeutic techniques. He believed people only change their minds when they feel understood and respected. So instead of attacking the opposing view, you:

- Show you genuinely understand why someone would believe the opposite

- Acknowledge where their concerns are valid

- Present your view as a potential solution that addresses their concerns too

- Propose a middle ground that gives both sides something

This isn't a weakness it's a strategy. When discussing highly controversial topics, coming in guns blazing just makes people defensive. Rogerian arguments lower those defenses.

Choose a controversial and debatable topic. You can get ideas from our argumentative essay topics blog.

Rogerian Argument Structure

Introduction

- Present the problem neutrally (don't take a side yet)

- Explain why finding common ground matters

- No thesis statement in the traditional sense

Summary of Opposing View

- Present the other side's position fairly and accurately

- Explain their reasoning (don't strawman them)

- Acknowledge where their concerns are legitimate

Statement of Understanding

- Show you genuinely understand why someone would hold that view

- Validate their values and concerns

- Build trust

Your Position

- Present your view as another valid perspective

- Show how it addresses some of the concerns from the other side

- Frame it as complementary, not contradictory (where possible)

Common Ground

- Identify shared values and goals

- Show where both sides actually agree

- Build a foundation for compromise

Proposed Compromise

- Offer a solution that gives both sides something

- Show how this middle path addresses concerns from both perspectives

- Make it feel like collaboration, not surrender

Conclusion

- Emphasize shared goals

- Restate the benefits of the compromise

- Call for cooperation

When to Use Rogerian Arguments

Rogerian works best when:

- The topic is highly emotional or polarized

- Your audience strongly disagrees with you

- There's legitimate reasoning on both sides

- Finding compromise is more important than "winning"

- You need to reduce hostility before making your case

Don't use Rogerian when:

- There's a clear factual right/wrong answer

- Compromise would be unethical or impractical

- Your audience is already neutral or agreeable

- You have definitive evidence that proves your side

Example: Rogerian Argument in Action

Topic: Should schools require students to say the Pledge of Allegiance Approach: Instead of arguing yes or no definitively, find middle ground. Structure: Intro: Acknowledge this is a deeply divisive issue about patriotism vs. free speech Opposing view (Pro-requirement): Explain why some believe mandatory pledge builds civic pride and national unity Understanding: Validate that wanting students to respect their country is admirable Your view (Anti-requirement): Explain concerns about forced patriotism and freedom of conscience Common ground: Both sides want students to be engaged citizens who care about their country Compromise: Make pledge available but voluntary, teach about its history and meaning, create alternative ways for students to show civic engagement Conclusion: This solution respects both patriotic values and individual freedom |

Why this works: This topic is emotionally charged and tied to identity. Trying to "win" just makes people defensive. The Rogerian approach finds a solution that both sides can live with.

Quick Comparison: When to Use Each Type

Before we get into the details, here's a snapshot of when each argument structure works best:

| Structure | Best For | Audience | Goal | Counterargument Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Clear-cut debates with definitive positions | Neutral or undecided audience | Prove your side is correct | Address and refute directly |

| Rogerian | Highly emotional or polarized topics | Hostile or strongly opposed audience | Find common ground and compromise | Present fairly, then offer middle path |

| Toulmin | Complex logical arguments with qualifications | Academic or analytical audience | Build airtight logical case | Acknowledge limitations while maintaining claim |

Quick decision guide:

- Your topic is straightforward (e.g., "Should college athletes be paid?") = Classical

- Your audience strongly disagrees with you (e.g., writing about gun control) = Rogerian

- Your argument has lots of nuance (e.g., "Under what conditions should euthanasia be legal?") = Toulmin

Need help structuring your specific essay? Check out our argumentative essay outline guide with templates for all three models.

Deadline Tomorrow and You Haven't Started?

Get a professionally structured argumentative essay in as little as 3 hours

Unlimited revisions for 14 days

Types of Argument Claims

An argument claim, often simply referred to as a "claim," is a “declarative statement or proposition put forward in an argument or discussion.”

It is the central point or argumentative essay thesis statement that the person making the argument is trying to prove or persuade others to accept.

Factual Claims

Factual claims are statements that assert something as a fact or reality. They are based on observable evidence and can be proven or disproven.

For example,

| "Water boils at 100 degrees Celsius at sea level" is a factual claim because it can be tested and confirmed. |

Value Claims

Value claims express personal opinions, preferences, or judgments about something. They are not about facts but about what someone believes is right, good, or important.

For instance,

| "Eating a balanced diet is healthier" is a value claim because it reflects an opinion about what constitutes a healthy diet. |

Policy Claims

Policy claims propose a specific course of action or advocate for a change in the way things are done. They are often found in discussions about laws, regulations, or actions that should be taken.

An example would be,

| "The government should invest more in renewable energy sources to combat climate change." |

Causal Claims

Causal claims assert a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more phenomena. They suggest that one thing is responsible for another.

For instance,

| "Smoking cigarettes increases the risk of lung cancer" is a causal claim because it links smoking to the likelihood of developing lung cancer. |

Definitional Claims

Definitional claims seek to clarify or establish the meaning of a term or concept. They aim to set a specific definition or understanding for a particular word or idea.

For example,

| "In this context, 'freedom' refers to the absence of coercion or restraint." This claim defines what 'freedom' means in the given discussion. |

Understanding these different types of argument claims can help you identify the nature of statements in discussions and debates. This makes it easier to analyze and respond to various arguments.

Additional Common Types of Arguments

Arguments can be classified into several types based on their structure, purpose, or logical form. Here are some more common types of arguments:

Deductive Arguments

These arguments aim to provide logically conclusive support for their conclusions. If the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. Examples include:

- Categorical Syllogisms (All A are B. All C are A. Therefore, all C are B.)

- Disjunctive Syllogisms (Either A or B. Not A. Therefore, B.)

- Hypothetical Syllogisms (If A then B. B. Therefore, A.)

- Modus Ponens and Modus Tollens (If A then B. A. Therefore, B.)

Inductive Arguments

These arguments aim to provide probable support for their conclusions. The premises provide evidence that makes the conclusion likely but not certain. Examples include:

- Generalizations (inductive reasoning)

- Statistical syllogisms

- Analogical arguments

Abductive Arguments

Also known as inference to the best explanation, abductive arguments propose that the best explanation for a set of evidence is a certain conclusion. It is commonly used in scientific reasoning.

Inference to the Best Explanation:

- Premise 1: The ground is wet.

- Premise 2: The weather report said it would rain today.

- Conclusion: Therefore, it probably rained recently.

This abductive argument suggests that rain is the best explanation for the observed wet ground.

Causal Arguments

These arguments aim to establish a causal relationship between two or more events or variables. They often use premises about regularities or mechanisms to support a causal claim.

- Premise: Smoking cigarettes is a known cause of lung cancer.

- Conclusion: Therefore, smoking cigarettes increases the risk of lung cancer.

This argument establishes a causal link between smoking and lung cancer based on known causal relationships.

Analogical Arguments

These arguments draw parallels between two similar cases and argue that what is true in one case is likely true in the other.

For Example;

- Premise 1: Humans have a respiratory system.

- Premise 2: Birds have a respiratory system.

- Conclusion: Therefore, birds are similar to humans in having a respiratory system.

This analogical argument draws a parallel between humans and birds based on a shared characteristic.

Teleological Arguments

These arguments reason from the purpose, design, or end goal of something to its characteristics or existence.

For Example;

- Premise: The universe exhibits complexity and order.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the universe must have been designed by an intelligent creator.

This teleological argument reasons that the existence of order and complexity in the universe implies a purposeful design.

Moral Arguments

These arguments aim to establish moral conclusions based on moral principles or judgments.

- Premise 1: Killing another human being is morally wrong.

- Premise 2: Euthanasia involves intentionally ending a human life.

- Conclusion: Therefore, euthanasia is morally wrong.

This moral argument derives a moral judgment about euthanasia based on general moral principles.

Evaluation Arguments

Evaluation arguments focus on assessing the quality, effectiveness, or value of something. They often involve making judgments based on criteria or standards. Here are the components of evaluation arguments:

- Subject

- Criteria

- Evidence

- Conclusion

To close your argument perfectly in conclusion, read our guide on argumentative essay conclusion.

Side by Side Comparison: All Three Structures

Let's see how the same topic would look using each structure.

| Topic: Should social media companies be held legally liable for content posted by users? |

Classical Approach

Structure:

Intro: Social media has become the public square; who's responsible for what's said there? Thesis: Social media companies should be held liable for illegal content to incentivize better moderation. Argument 1: Current Section 230 protections allow harmful content to spread unchecked Argument 2: Platforms profit from engagement, including from harmful content Argument 3: Liability would motivate better moderation systems Counterargument: "But this would destroy free speech" = Explain how targeted liability doesn't prevent legal speech Conclusion: Accountability is necessary for public safety |

Tone: Definitive, confident, persuasive

Rogerian Approach

Structure:

Intro: This debate pits free speech against safety both vital values View 1 (Pro-immunity): Explain why some believe platforms need protection to allow free expression and avoid censorship Understanding: Acknowledge that preserving spaces for open dialogue matters View 2 (Pro-liability): Explain concerns about harmful content and platform accountability Common ground: Both sides want vibrant public discourse that doesn't cause real-world harm Compromise: Graduated liability based on company size and nature of content; safe harbors for good-faith moderation efforts Conclusion: Balanced regulation protects both expression and safety |

Tone: Diplomatic, balanced, collaborative

Toulmin Approach

Structure:

Claim: Social media platforms should face limited liability for illegal content when they have knowledge of it and fail to act. Grounds: Current immunity allows platforms to ignore clearly illegal content without consequence. Warrant: If platforms know about illegal content and don't remove it, they're facilitating that illegal activity. Backing: Offline publishers have always been held to this standard; online platforms shouldn't be completely exempt. Qualifier: This applies specifically to clearly illegal content (not opinions), when the platform has been notified, and when reasonable action is possible. Rebuttal: In cases where content is ambiguous, where the platform wasn't notified, or where the volume makes moderation impossible, immunity should remain. Conclusion: Targeted liability creates accountability without destroying the internet. |

Tone: Analytical, precise, qualified

Common Mistakes with Each Structure

Classical Argument Mistakes

Strawmanning the counterargument: Don't make the opposing view sound stupid. Present it fairly, THEN refute it

Refuting too early: Don't address counterarguments in your intro, build your case first, THEN handle objections

Weak or missing counterargument section: Ignoring the other side makes you look naive. Address the strongest opposing points, not the weakest

Rogerian Argument Mistakes

Sounding wishy-washy: Finding common ground doesn't mean you have no position. You can be diplomatic and still have a strong view

Proposing impossible compromises: Your middle ground needs to be actually workable. "Let's just all get along" isn't a solution

Using Rogerian for clear-cut issues: Some things don't have a middle ground. "Should murder be legal?" doesn't need Rogerian approach

Toulmin Argument Mistakes

Over-complicating simple arguments: Not every claim needs a six-part breakdown. Use Toulmin when nuance actually matters

Forgetting the warrant: Stating grounds without explaining their connection to your claim. The warrant is what makes Toulmin different from just "claim + evidence."

Qualifying yourself into irrelevance: Don't add so many qualifiers that your claim becomes meaningless. "In some cases, possibly, maybe..." = weak argument

Final Thoughts

Argument structure is strategy, not formula. You're not just checking boxes you're building a case designed to persuade a specific audience about a specific issue.

Classical gives you a proven framework for most topics. Rogerian helps you navigate controversial territory without starting a fight. Toulmin lets you build airtight logic for complex claims.

The key is matching structure to situation:

- What are you arguing?

- Who are you arguing to?

- What do you want them to do with your argument?

Answer those questions, and the right structure becomes obvious.

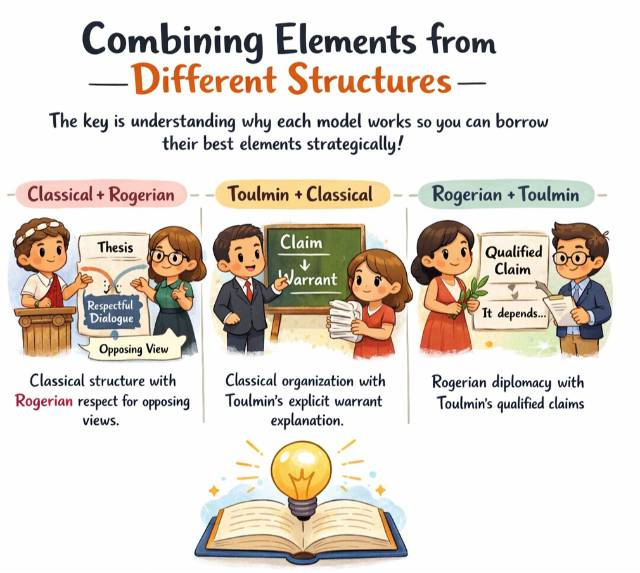

| Remember: structure is a tool, not a straitjacket. Once you understand why each model works, you can adapt them to fit your specific needs. The best arguments often borrow elements from multiple structures strategically. |

Now you know how to organize your argument. Time to actually write it.

Still struggling with your essay?

Stop struggling with structure and organization. Our expert writers deliver:

- Custom essays on any topic

- Perfectly organized chronological outlines

- Clear, engaging writing that follows all academic standards

- 100% original content with zero AI detection

From outline to final draft, we handle every step.

Get Started Now

-20402.jpg)

-20437.png)