Analytical Essay Example 1: Social Media's Impact

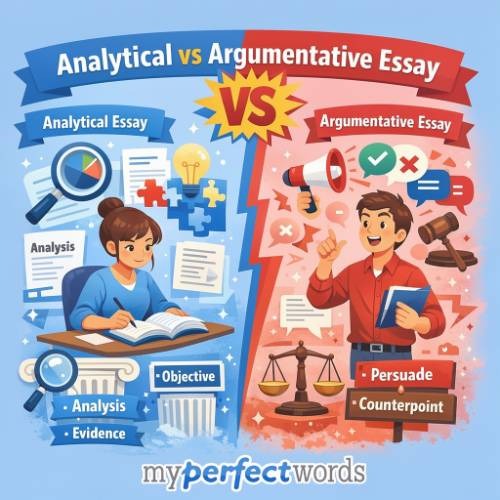

Here's a complete analytical essay examining social media's effect on teen mental health. Notice how each paragraph connects evidence back to the thesis. Also, check out our guide on analytical vs argumentative essays to understand the key differences before you start writing.

The Hidden Cost: How Social Media Algorithms Amplify Teen Anxiety

Introduction

Every morning, millions of teenagers wake up and immediately check their phones, scrolling through carefully curated feeds that seem to showcase everyone else living their best lives. While social media platforms promise connection and community, recent research reveals a darker pattern: the algorithmic systems designed to maximize engagement are systematically amplifying anxiety and depression among adolescent users. By examining how recommendation algorithms, comparison-based metrics, and constant availability create psychological pressure, this analysis demonstrates that social media's impact on teen mental health is not merely a byproduct of usage but an intentional consequence of platform design.

Body Paragraph 1

Social media algorithms prioritize content that generates strong emotional responses, which disproportionately means anxiety-inducing material. A 2023 study published in JAMA Psychiatry found that Instagram's recommendation algorithm showed users 73% more content related to topics they'd previously engaged with emotionally, even when that content triggered negative feelings. For teenagers already struggling with self-image issues, this creates a feedback loop: viewing one post about body image leads the algorithm to serve dozens more, intensifying insecurity rather than providing diverse content. The algorithm doesn't care about user wellbeing; it cares about engagement metrics. Each additional minute of scrolling represents advertising revenue, which means platforms are financially incentivized to deliver content that keeps users anxious and checking back for more. This design choice transforms what could be neutral technology into a system that actively worsens teen mental health.

Body Paragraph 2

Beyond algorithmic amplification, social media's quantification of social validation through likes, comments, and follower counts creates measurable anxiety. Traditional social interactions involve subjective feedback, but social media reduces acceptance to numerical metrics that teenagers check compulsively. Research from Stanford's Social Media Lab demonstrates that 68% of teenagers report feeling anxious when posts receive fewer interactions than expected, with some checking engagement metrics over 30 times per day. This constant evaluation creates what psychologists call "performance anxiety," the fear that one's social worth can be calculated and found lacking. When a post receives low engagement, teenagers don't just feel disappointed; they internalize it as quantifiable evidence of social failure. The visibility of others' higher metrics intensifies this anxiety, creating a competitive environment where self-worth becomes tied to algorithmic popularity contests that platforms engineer to be unwinnable.

Body Paragraph 3

The third mechanism amplifying teen anxiety is social media's elimination of temporal boundaries around social interaction. Previous generations could leave school and escape peer judgment until the next day, but smartphones mean social dynamics now operate 24/7. A teenager can wake up at 3 AM to find group chats discussing events they weren't invited to, or discover posts that feel like deliberate exclusion. The FOMO (fear of missing out) that social media generates isn't just about missing activities; it's about constant exposure to evidence of social life happening without you. Dr. Jean Twenge's longitudinal study found that teenagers who spend more than 5 hours daily on social media are 71% more likely to show suicide risk factors than those who spend less than one hour, with constant availability identified as a key stressor. The inability to ever fully disconnect means anxiety has no off switch, transforming teenage social life from intermittent stress to chronic psychological pressure.

Conclusion

Social media platforms have engineered an environment where teen anxiety isn't an unfortunate side effect but a predictable outcome of deliberate design choices. Algorithms that prioritize engagement over wellbeing, metrics that quantify social worth, and constant connectivity that eliminates recovery time combine to create unprecedented psychological pressure on developing minds. While social media companies claim to value user safety, their business model depends on the exact behaviors that research consistently links to increased anxiety and depression. Addressing this crisis requires more than teaching digital literacy to teenagers; it demands fundamental changes to how platforms operate, including algorithmic transparency, engagement metric reforms, and built-in boundaries that protect teenage users from systems designed to exploit their vulnerabilities. Until that happens, the hidden cost of every scroll continues to compound.

Why This Example Works:

This essay moves beyond describing social media's effects to arguing they're "intentional consequences of platform design." Notice how each body paragraph tackles one mechanism (algorithms, metrics, constant availability) with specific research data, then explains WHY that mechanism creates anxiety rather than just stating effects. The 73% algorithm statistic becomes meaningful only when the writer explains the feedback loop it creates. The conclusion shifts from summarizing points to proposing policy solutions, showing analysis can drive action.

Notice how the introduction's thesis statement clearly establishes the essay's analytical direction, arguing that social media's harm is 'intentional' rather than accidental. Crafting thesis statements that make arguable claims like this takes practice.

If you're struggling to move from topic to argument, our guide on analytical essay thesis statements breaks down exactly how to write thesis statements that set up strong analysis with the what, how, and so what framework.

Analysis Paper Example 2: Climate Policy Effectiveness

This analysis paper example evaluates carbon pricing policies using multiple research sources. Watch how it builds an argument through systematic evidence evaluation.

Carbon Pricing: Why Market Based Climate Solutions Fail to Address Scale

Introduction

Economists have long championed carbon pricing, whether through carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems, as the most efficient mechanism to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The theory appears elegant: assign a cost to pollution, and markets will naturally optimize toward cleaner alternatives. However, examining carbon pricing's implementation across multiple jurisdictions over the past two decades reveals a troubling pattern: while these policies generate revenue and create modest emission reductions, they consistently fail to achieve the rapid, large-scale decarbonization that climate science demands. By analyzing price levels, political constraints, and substitution effects in existing carbon pricing systems, this analysis demonstrates that market-based climate solutions are structurally incapable of delivering change at the pace and scale required, revealing fundamental limits of treating atmospheric carbon as simply another commodity to be priced.

Body Paragraph 1

Carbon pricing systems consistently set prices far below the levels economists calculate would drive meaningful behavior change, rendering them symbolically significant but practically inadequate. The European Union's Emissions Trading System (ETS), often cited as the world's most successful carbon market, operated for its first decade with prices averaging €7-15 per ton, well below the €40-80 per ton range the EU's own analysis indicated would drive substantial emissions reductions. Even after recent reforms pushed prices to €80-100 per ton, modeling from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research shows that achieving Paris Agreement targets would require prices of €200+ per ton by 2030. This consistent underpricing isn't accidental; it reflects political reality. British Columbia's carbon tax, another frequently celebrated policy, was explicitly capped at levels designed to be "revenue neutral" and "not hurt the economy," which meant pricing carbon at levels too low to significantly alter fossil fuel consumption. The gap between economically rational pricing and politically achievable pricing reveals a structural flaw: carbon pricing can only work if prices are high enough to fundamentally reshape economic incentives, but democracies consistently refuse to set prices at those levels because voters correctly perceive them as economically disruptive.

Body Paragraph 2

Beyond inadequate pricing, carbon pricing systems face a second structural limitation: they reduce emissions primarily through efficiency improvements rather than wholesale energy transition. California's cap-and-trade program, operational since 2013, has indeed reduced emissions, but analysis by UC Berkeley researchers shows that 60% of reductions came from efficiency upgrades to existing fossil fuel infrastructure rather than shifts to renewable energy. Industries bought permits and optimized combustion processes rather than fundamentally changing energy sources. This pattern repeats globally: carbon pricing encourages marginal improvements but rarely triggers the transformative investments needed for deep decarbonization. The reason is economic logic: under carbon pricing, the rational business response is to reduce emissions to the point where abatement costs equal carbon prices, then stop. If carbon is priced at €80 per ton, companies will implement any efficiency measures costing less than €80 per ton of CO2 avoided, but won't make the much larger, riskier investments required to eliminate fossil fuels entirely. This creates a predictable ceiling on emissions reductions, with carbon pricing systems delivering improvements of 10-30% rather than the 100% decarbonization that climate goals require.

Body Paragraph 3

The third limitation becomes apparent when examining carbon pricing's geographic constraints: even successful systems in one jurisdiction drive emissions to others rather than eliminating them globally. When the EU implemented carbon pricing without equivalent border adjustments, energy-intensive industries relocated to regions without carbon constraints: a phenomenon economists call "carbon leakage." Research published in Nature Climate Change found that 20-25% of emissions reductions within EU carbon pricing systems were offset by increased emissions in countries like China and India, where relocated industries operated under no carbon constraints. Some economists argue that border carbon adjustments could solve this problem, but the political and legal challenges of implementing such measures are immense, as evidenced by the EU's decade-long struggle to design border adjustment mechanisms that comply with WTO rules. This reveals carbon pricing's fundamental geographic problem: treating carbon as a commodity with a price only works if that price applies globally and uniformly, but the political and economic realities of sovereign nations make universal carbon pricing nearly impossible to achieve. As long as some jurisdictions offer lower or no carbon prices, market forces will route emissions to those locations rather than eliminating them.

Conclusion

Carbon pricing's theoretical elegance dissolves when confronted with practical implementation. Political systems consistently set prices too low to drive transformation, economic logic limits reductions to efficiency improvements rather than wholesale change, and geographic fragmentation allows emissions to relocate rather than disappear. These aren't implementation failures that better policy design might fix; they're structural limitations inherent to market-based climate solutions. This doesn't mean carbon pricing has no role; modest carbon prices can fund green investment and send directional signals about future costs. But evidence increasingly suggests that achieving necessary emissions reductions requires approaches that carbon pricing cannot deliver: direct regulation mandating clean energy deployment, public investment in infrastructure transformation, and industrial policy actively building zero-carbon alternatives. The market's invisible hand, even when guided by carbon prices, moves too slowly and too weakly to address a crisis requiring rapid, comprehensive change.

Why This Example Works:

This writer doesn't just claim carbon pricing fails, they systematically show why it CAN'T work at necessary scale. Watch how they handle the EU ETS: presents the €7-15 actual prices, contrasts with €200+ needed prices, then explains the political impossibility of that gap. Each body paragraph examines a different structural barrier (pricing, substitution, geography). When addressing "revenue neutral" policies or border adjustments, the writer explains why these supposed solutions don't solve the core problems. The conclusion distinguishes carbon pricing's possible modest role from the transformation it can't deliver.

Analysis Essay Example 3

Critical analysis goes beyond summary to evaluate strengths, weaknesses, and implications. Here's an example analyzing a research study's methodology.

Evaluating Marshmallow Test Replication: Why Context Matters More Than Willpower

Introduction

The Stanford marshmallow experiment, which purported to show that childhood self-control predicts life outcomes decades later, has become one of psychology's most famous studies and most widely misinterpreted. When researchers claimed that four-year-olds' ability to delay eating a marshmallow correlated with higher SAT scores and better adult outcomes, the finding seemed to validate narratives about willpower as destiny. However, a 2018 replication study by Watts, Duncan, and Quan published in Psychological Science reveals critical flaws in both the original research design and its interpretation. By examining sample selection bias, confounding variables, and effect size limitations in the replication study, this critical analysis demonstrates that the marshmallow test measures family socioeconomic status and childhood stability more than innate self-control, exposing how a methodologically flawed study shaped decades of policy discourse about individual responsibility versus structural support.

Body Paragraph 1

The original marshmallow study's most significant flaw was its small, highly unrepresentative sample: a limitation the 2018 replication made glaringly obvious. Mischel's original research tested fewer than 90 children, primarily from Stanford's campus preschool, meaning participants came overwhelmingly from educated, affluent families. The replication study used 918 children from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and found dramatically different results: when controlling for family income, maternal education, and home environment, the correlation between delayed gratification and later outcomes dropped by 70%. This reveals that the original study wasn't measuring pure willpower, it was measuring which children had experienced enough stability and resource security to trust that promised rewards would materialize. A four-year-old from a chaotic, resource-scarce environment rationally chooses immediate gratification because their experience teaches that future promises are unreliable. The original study's sample bias meant it captured privilege rather than psychology, but because findings aligned with cultural beliefs about individual merit, this fundamental flaw went unexamined for decades.

Body Paragraph 2

Beyond sample issues, the replication study exposed how the original research failed to account for obvious confounding variables. Mischel's team treated delayed gratification as an independent variable, a stable trait children either possessed or lacked, but the replication data shows it's heavily influenced by environmental factors. Children's performance on the marshmallow test varied significantly based on whether they'd eaten recently, how stable their home environment was, and whether they'd previously experienced broken promises from adults. The replication found that home environment factors alone explained 2-3 times more variation in later outcomes than marshmallow test performance did. This means the original study's causal claim, that self-control causes better outcomes, was unjustified. Both the ability to delay gratification and later success might result from the same underlying cause: growing up in a stable, supportive environment with adequate resources. The original researchers' failure to measure and control for these variables wasn't just a minor oversight, it invalidated their core conclusion about self-control as a personality trait determining life trajectories.

Body Paragraph 3

The final critical weakness the replication revealed was the original study's dramatic overstatement of effect sizes. Popular accounts describe the marshmallow test as powerfully predictive, with children who delayed gratification achieving vastly superior outcomes. The replication data tells a more modest story: even before controlling for confounding variables, marshmallow test performance explained only about 6% of variance in academic achievement at age 15: a statistically significant but practically limited relationship. After adjusting for family background, the explained variance dropped below 2%. To put this in perspective, family income alone explained four times more variation in outcomes than delayed gratification did. Yet the original study's findings were translated into policy recommendations about teaching self-control to disadvantaged children, as if willpower training could substitute for economic support. This represents a critical failure of science communication: a small, noisy correlation in an unrepresentative sample became simplified into a deterministic narrative that justified reducing structural investment in favor of individual behavioral intervention.

Conclusion

The marshmallow test replication doesn't just correct an old study; it reveals how methodological limitations, when combined with cultural narratives people want to believe, can shape policy for decades despite weak evidentiary foundations. The original research suffered from small sample size, lack of demographic diversity, failure to control confounding variables, and overstated effect sizes. The replication study exposed these flaws while showing that what the marshmallow test actually measured was childhood stability and resource access, not innate personality traits. This has implications beyond just psychology: it demonstrates how incomplete science, when it aligns with ideological preferences for individual responsibility over structural investment, can persist unquestioned and influence everything from parenting advice to education policy. Rigorous replication and methodological scrutiny aren't optional refinements; they're essential safeguards against building policy on foundations of appealing but inaccurate claims.

Why This Example Works:

The writer takes a clear position, this study was "methodologically flawed," then systematically demonstrates each flaw. Notice how they handle the sample bias: first presents Mischel's 90 privileged children, then contrasts with the replication's 918 diverse children, then explains the 70% correlation drop. They acknowledge the replication found SOME correlation (6% variance) before showing why that's practically insignificant compared to family income's effect. The tone stays analytical rather than attacking, explaining how sample bias could persist "because findings aligned with cultural beliefs about individual merit."

If you have not selected a topic, visit our analytical essay topics blogs before proceeding to the next example.

Analysis Essay Example 4

Textual analysis examines how language creates meaning. This example analyzes word choice, tone, and structure in a famous speech excerpt.

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address: How Syntax Creates Transcendence

Introduction

The Gettysburg Address, delivered in November 1863, lasted barely two minutes yet became one of history's most analyzed speeches. While many focus on its brevity or historical context, the speech's enduring power comes from Lincoln's precise manipulation of syntax: how sentence structure itself creates meaning. By examining his use of parallel construction, strategic repetition, and the shift from past to present to future tense, this textual analysis reveals how Lincoln's grammatical choices transformed a battlefield dedication into a statement of national purpose, using sentence structure to move listeners from mourning to commitment within just 272 words.

Body Paragraph 1

Lincoln's opening sentence establishes his rhetorical strategy through parallel construction: "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." The syntax does two things simultaneously. First, "conceived" and "dedicated" create grammatical parallelism suggesting the nation's founding was both biological birth and moral commitment. Second, the sentence structure delays the subject ("a new nation") until after establishing temporal and geographic context, forcing listeners to wait for the declaration, a delay that creates emphasis through anticipation. The choice of "four score and seven" rather than "87" matters: biblical phrasing elevates the moment from mundane history to sacred narrative. Even word order contributes: placing "Liberty" before "all men are created equal" suggests freedom precedes equality rather than following from it, a subtle but significant philosophical claim embedded in syntax.

Body Paragraph 2

The second paragraph's famous repetition, "we can not dedicate we can not consecrate we can not hallow this ground", uses negative parallel structure to intensify meaning through accumulation. Each verb slightly escalates: "dedicate" suggests assignment of purpose, "consecrate" adds religious significance, and "hallow" implies the sacred made tangible. By repeating "we can not" three times before explaining why, Lincoln creates rhythmic power while building to his central point: "The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract." The sentence structure performs its meaning, the struggle to articulate adequacy mirrors the inadequacy being described. Notice also the deliberate ambiguity of "living and dead": the syntax places them in grammatical equality, collapsing temporal distinction between present and past, suggesting sacrifice continues to act in the present moment.

Body Paragraph 3

The final paragraph shifts from past tense to future imperative through careful syntactic progression: "It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work." The structure of "for us the living" deliberately mirrors the earlier "living and dead," transferring burden from the deceased to survivors. Then comes the speech's most complex sentence: "It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion." The nested structure, with a dash separating independent clauses, forces listeners to hold two ideas in tension, dedication and its source, before Lincoln completes the thought. The repetition of "devotion" creates sonic and conceptual circularity: the dead's devotion generates our devotion, which continues their work. The syntax suggests endless cycle rather than closed ending.

Conclusion

Lincoln's grammatical choices in the Gettysburg Address transform syntax into argument. Parallel construction elevates founding principles, negative repetition builds emotional power, and tense shifts move audiences from past commemoration to future commitment. Each sentence's structure reinforces its meaning: delayed subjects create emphasis, nested clauses suggest complexity, and repeated words form sonic patterns that make ideas memorable. This textual analysis reveals that the Address's power isn't merely what Lincoln said but how sentence structure shaped listeners' emotional and intellectual journey through his argument. Great rhetoric doesn't just select right words, it arranges them in sequences that make ideas feel inevitable.

Why This Example Works:

This analysis examines how sentence structure creates meaning in the Gettysburg Address. Watch how the writer handles "we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow": they don't just identify repetition, they show how each verb escalates and how the triple negative builds to the positive claim that the soldiers already consecrated the ground. The writer quotes Lincoln's exact phrasing, then analyzes word choices like "minute" and "far away" to show spatial symbolism. Notice the focus on syntax rather than just content.

Analysis Essay Example 5

Analyzing a news article? This example examines bias, evidence quality, and argumentation in a magazine piece.

Deconstructing "The Case Against Homework": When Anecdote Replaces Evidence

Introduction

A 2024 Atlantic article titled "The Case Against Homework" argues that homework provides minimal academic benefit while causing family stress and inequality. The piece resonated widely, generating thousands of shares and citations in school board debates nationwide. However, examining the article's argumentation reveals significant problems: selective evidence presentation, conflation of homework quantity with homework quality, and logical leaps from correlation to causation. While the author raises legitimate concerns about homework's unequal impact across socioeconomic groups, the analysis demonstrates how an opinion piece can shape public discourse by packaging weak argumentation in compelling narrative, substituting emotional appeals and anecdotal evidence for the systematic analysis its policy recommendations would require.

Body Paragraph 1

The article's central evidentiary problem is cherry-picking research while ignoring contradictory findings. The author cites a 2006 Duke University study showing weak correlations between homework and elementary student achievement, presenting this as definitive proof homework is ineffective. However, the article entirely omits mentioning that the same research found strong positive correlations for high school students, or that the researcher explicitly stated homework's effectiveness depends on type, duration, and implementation, not whether homework exists at all. By extracting one finding from a nuanced study while ignoring the researcher's own interpretive caution, the article creates a false sense of scientific consensus. Further investigation reveals the author consulted primarily with advocates who oppose homework rather than researchers studying it systematically. This isn't balanced journalism, it's advocacy journalism presenting one side's arguments as established fact.

Body Paragraph 2

Beyond selective citation, the article commits a logical fallacy by conflating all homework as equivalent. When arguing homework increases inequality, the author describes students spending hours on worksheets while parents without college education struggle to help with advanced math. These anecdotes may be true, but they describe badly designed homework, repetitive busywork requiring parent expertise, not homework generally. Research distinguishes between mindless repetition and thoughtful practice, between homework requiring parent involvement and homework building independent skills. The article ignores these distinctions, instead arguing that because some homework is poorly designed, all homework should be eliminated. This reasoning is like arguing that because some teaching is ineffective, schools should eliminate instruction entirely. The logical structure reveals itself: begin with legitimate concerns about homework quality and inequality, then leap to conclusions about homework existence without establishing the connection between the two.

Body Paragraph 3

The article's most problematic element is its unexamined premise that family time and academic development are zero-sum tradeoffs. The author presents moving stories of families whose evenings dissolve into homework battles, positioning homework as stealing time from important parent-child connection. While acknowledging these experiences are real, the framing ignores that some homework might facilitate family interaction, such as reading together, discussing current events, or parents helping children develop organizational skills. The binary choice the article presents, homework OR family time, oversimplifies reality. Many families find ways to integrate both, and research on homework's effects consistently notes that parental involvement in homework, when supportive rather than pressuring, correlates with positive academic and social outcomes. By framing the debate as family wellbeing versus academic demands, the article manufactures conflict rather than analyzing how these goals might coexist or reinforce each other.

Conclusion

This article analysis reveals how persuasive writing can substitute narrative power for analytical rigor. By selectively presenting evidence, conflating homework quality with homework existence, and framing false binaries between family time and learning, the article builds an emotionally compelling case on logically weak foundations. This matters because articles like this shape policy debates: school boards cite it, parents reference it, and advocacy groups distribute it as evidence. The article raises important questions about homework's design and equitable implementation, but answering those questions requires the systematic analysis the piece avoids. Effective policy requires distinguishing between problems with homework's implementation versus its existence, between correlation and causation, and between anecdotal experiences and representative data. This article provides none of that, it provides a well-written opinion masquerading as analysis, demonstrating why media literacy requires examining not just what sources say but how they build their arguments.

Why This Example Works:

The writer identifies three specific logical problems in The Atlantic article: cherry-picking research (citing Duke's elementary findings while ignoring high school results), conflating homework quality with homework existence, and creating false binaries (family time OR learning). Notice how they acknowledge the article's legitimate concerns about inequality before showing why the argumentation doesn't support the proposed solution. The analysis explains how "moving stories of families" function rhetorically, creating emotional impact that substitutes for systematic evidence.

Fast Analytical Essay HELP

Meet Tight Deadlines Without Sacrificing Quality

unlimited revisions

Analysis Essay Example 6

Issue analysis examines complex problems systematically. This example analyzes the college affordability crisis using economic and policy evidence.

The Student Debt Crisis: Why "Personal Responsibility" Misdiagnoses Structural Problems

Introduction

Politicians and commentators frequently frame student debt as a personal responsibility issue; students chose expensive schools, borrowed too much, or pursued unmarketable degrees. This framing suggests individual decision-making errors rather than systemic problems. However, examining tuition trends, wage stagnation, and state funding cuts over the past four decades reveals that student debt is primarily a structural crisis caused by policy choices that shifted higher education costs from public investment to individual burden. By analyzing how state disinvestment, tuition inflation outpacing income growth, and predatory lending practices interact, this analysis demonstrates that student debt represents wealth extraction from younger generations rather than individual financial irresponsibility, requiring policy solutions rather than lectures about better choices.

Body Paragraph 1

The crisis begins with state disinvestment in public higher education. In 1980, state governments funded approximately 75% of public university operating costs, with students covering 25% through tuition. By 2020, those ratios reversed: states funded roughly 25% while tuition covered 75%. Data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association shows that inflation-adjusted state funding per student dropped 37% between 2008 and 2020 alone. This wasn't inevitable; it reflected deliberate policy choices to cut education budgets during recessions without restoring funding during recoveries. The result was predictable: universities increased tuition to maintain operations, directly transferring costs to students. When critics blame students for "choosing expensive schools," they ignore that public universities, traditionally the affordable option, now charge tuition that matches or exceeds inflation-adjusted private school costs from previous generations. The personal responsibility framework treats as individual choice what is actually policy-driven cost-shifting.

Body Paragraph 2

Compounding disinvestment is wage stagnation that makes it impossible for students to "work their way through college" as previous generations claim they did. Federal minimum wage data adjusted for inflation shows that a 1980 minimum-wage worker could pay for a year of public university tuition with approximately 300 hours of work, roughly a summer job. By 2020, that same tuition required 2,300 hours at minimum wage, more than a full-time year-round job. This calculation understates reality because it ignores rent, food, and other costs that have also increased faster than wages. Research from Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce found that 70% of students now work while enrolled, with 40% working full-time, yet still graduate with significant debt. The "work harder" advice assumes an economic reality that no longer exists. Students are working, it's just that work no longer covers costs that have inflated far beyond wage growth.

Body Paragraph 3

The third structural component is predatory lending practices that profit from students' limited options. Federal student loans charge 4-7% interest rates despite having default rates under 10% and using government backing that eliminates lender risk. Private loans charge even higher rates while offering no income-based repayment or forgiveness options. More perniciously, student debt is uniquely exempt from bankruptcy protection: a 2005 policy change lobbied for by lenders that creates permanent debt obligations even when borrowers face catastrophic circumstances. This isn't normal lending where creditors assess risk and price accordingly, it's guaranteed profit extraction from borrowers who have no alternative and no escape. The lending system treats education as a profit center rather than public investment, with interest payments transferring wealth from young people to financial institutions for decades after graduation.

Conclusion

Student debt isn't a personal responsibility failure; it's the predictable outcome of state disinvestment, wage stagnation, and predatory lending combining to make higher education unaffordable through traditional means. When states cut funding, universities raised tuition. When wages stagnated, working through school became impossible. When borrowing became the only option, lenders imposed terms that maximize profit extraction. This analysis reveals how treating structural problems as individual failures serves political purposes: it justifies inaction by blaming victims while obscuring the policy choices that created the crisis. Solving student debt requires reversing those policy choices, restoring public funding, raising wages, and reforming lending practices, not lecturing students about personal responsibility in an economic environment deliberately designed to make affordable education impossible without borrowing.

Why This Example Works:

This essay challenges the "personal responsibility" framing by showing three structural causes. Watch the state funding reversal: 75% state / 25% student in 1980 flipped to 25% state / 75% student by 2020: concrete numbers making the shift visible. The writer calculates that minimum wage work required 300 hours for tuition in 1980 versus 2,300 hours in 2020, showing "work your way through college" became mathematically impossible. Each body paragraph tackles one structural barrier, then the conclusion connects back to showing why "personal responsibility" advice misdiagnoses the problem.

Analytical Essay Introduction Example

Struggling with your intro? Here are 3 strong openings with annotations showing what makes them work.

Example 1: Hook with a Question

"Why do dystopian novels surge in popularity during times of political upheaval? From Orwell's 1984 selling out after the 2016 election to The Handmaid's Tale dominating bestseller lists during abortion debates, dystopian fiction seems to resonate most when readers recognize uncomfortable parallels to their present reality. By examining how Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale uses religious fundamentalism, reproductive control, and normalized violence to critique contemporary political movements, this analysis demonstrates that dystopian fiction's power lies not in predicting the future but in defamiliarizing the present, making visible the authoritarian patterns we might otherwise rationalize as normal."

What works here:

This introduction opens with "Why do dystopian novels surge..." creating immediate curiosity. The writer provides contemporary examples (1984 selling out after 2016) that readers recognize, establishing relevance before narrowing to The Handmaid's Tale specifically. The thesis appears in the final sentence, arguing dystopian fiction "defamiliarizes the present" rather than predicts the future, a specific analytical claim about the genre's function.

Example 2: Hook with Context

"Before the Industrial Revolution, most writing served practical purposes, such as legal documents, religious texts, and personal correspondence. The idea that ordinary people might read for pleasure, and that authors might write primarily to entertain or provoke thought rather than record information, emerged alongside mass literacy and affordable printing. This shift transformed not just what people read but how they understood narrative itself. By examining how Charles Dickens serialized Great Expectations to create suspense, develop characters gradually, and respond to reader feedback, this analysis reveals how 19th-century publishing constraints didn't limit storytelling: they created the multi-layered narrative techniques that modern novels still employ, demonstrating that formal innovations often emerge from practical constraints rather than despite them."

What works here:

Opening with pre-Industrial Revolution context establishes how narrative reading itself evolved, preparing readers for the analysis of serialization's impact. The writer moves from broad history (writing's purposes) to specific case (Dickens' Great Expectations) to focused thesis (constraints created rather than limited narrative techniques). This progression narrows from general context to specific argument systematically.

Key takeaway: Every analytical essay introduction needs Hook, Context, and Thesis, but HOW you hook depends on your topic and audience.

Analysis Paragraph Example (Body Paragraphs)

Body paragraphs are where analysis happens. Here's a strong example showing structure in action.

Example Paragraph: Analyzing Symbolism in The Great Gatsby

Fitzgerald uses the green light to symbolize Gatsby's unattainable dreams, with its physical distance across the water representing the unbridgeable gap between his present reality and impossible aspirations.

In the novel's first mention, Nick observes Gatsby at night: "He stretched out his arms toward the dark water in a curious way... I could have sworn he was trembling. Involuntarily I glanced seaward and distinguished nothing except a single green light, minute and far away, that might have been the end of a dock" (Fitzgerald 21).

This physical reaching toward something distant mirrors Gatsby's emotional state, always striving for a dream that remains just beyond reach. The "trembling" suggests vulnerability beneath his confident exterior, revealing genuine longing rather than mere obsession. Fitzgerald's word choice emphasizes distance: the light is "minute," "far away," and requires effort to distinguish. Gatsby can see his goal but never grasp it, foreshadowing his ultimate failure. The spatial relationship between Gatsby and the light literalizes his psychological distance from Daisy and everything she represents.

This pattern of visible but unreachable goals continues throughout the novel, with the green light reappearing at crucial moments when Gatsby's dreams seem closest to realization yet remain ultimately impossible.

What this paragraph works:

Notice the flow: opening sentence states the analytical claim about symbolism, quote provides textual evidence, then multiple sentences unpack what Fitzgerald's word choices reveal. The writer examines specific words, "trembling," "minute," "far away," showing how Fitzgerald creates symbolic meaning through precise language. The final sentence connects back to show this isn't isolated observation but part of the novel's larger pattern. The analysis section is longer than the evidence quote, keeping the focus on interpretation rather than quotation.

Short Analytical Essay Example (500 Words)

Need a shorter example? Here's a complete 500-word analytical essay you can use as a model.

Why Jaws Worked: The Power of What You Don't Show

The mechanical shark in Steven Spielberg's Jaws malfunctioned constantly during filming, forcing the director to suggest the shark's presence rather than showing it. This technical limitation became the film's greatest strength. By examining how Spielberg uses point-of-view shots, reaction shots, and John Williams' score to build dread without showing the threat, this analysis demonstrates that horror's power comes from audience imagination rather than visible monsters, revealing why Jaws remains terrifying while films with more elaborate effects feel dated.

The film's most famous sequence, the July 4th beach attack, demonstrates how suggestion creates terror. Spielberg cuts between the crowded beach, concerned Chief Brody, and underwater point-of-view shots gliding through the water. We see Brody's face tense, hear Williams' ominous two-note theme, watch the water churn, and see swimmers' panicked reactions, but the shark remains invisible. Our imagination fills the gap with something more frightening than rubber and machinery could provide. The shark's absence forces audiences to actively construct the threat, making each viewer's experience uniquely terrifying based on their personal fears.

Reaction shots amplify this effect. Instead of showing violence, Spielberg shows people watching violence. When the shark kills the Kintner boy, the camera focuses on horrified bystanders and the boy's mother realizing what's happened. Her scream tells us everything without graphic imagery. This technique exploits a psychological truth: we find others' terror more disturbing than direct violence. Watching someone else's horror triggers our mirror neurons and empathy systems more effectively than watching an animatronic creature. Spielberg understood that showing people react to a monster is scarier than showing the monster itself.

The film's third technique is sound design. Williams' score becomes so associated with danger that the two-note theme creates anxiety even during scenes with no shark. Spielberg deliberately uses the music sparingly, making its absence in some underwater scenes even more unsettling: we expect the warning but don't receive it, creating additional uncertainty. The score trains audiences to anticipate attacks, turning every underwater shot into potential threat regardless of whether the shark appears. This Pavlovian conditioning means the film controls audience anxiety through sound rather than special effects.

Jaws' accidental innovation, suggesting threats rather than showing them, reveals why many modern horror films fail despite superior technology. When audiences see every detail of a monster or ghost, imagination shuts down. We evaluate special effects rather than experiencing fear. Jaws works because it respects a fundamental principle: what audiences imagine is always more frightening than what filmmakers can show. The malfunctioning shark forced Spielberg to trust audience psychology over technical spectacle, creating a template that remains effective 50 years later. Horror doesn't require better effects, it requires understanding how human perception and imagination construct fear.

What works here:

Each body paragraph analyzes one technique, point-of-view shots, reaction shots, and sound design, and explains how that technique forces the audience to imagine the threat. The July 4th beach scene becomes terrifying not through spectacle but through Brody’s reactions, underwater movement, and the absence of the shark itself. The discussion of John Williams’ score shows how sound conditions audience fear even when nothing is visible. The conclusion connects this accidental limitation to a broader insight about horror, showing how the example’s analysis leads to a clear, defensible claim rather than a simple film description.

For a more indepth understanding, browse our analytical essay outline? to learn the essential components to include in your essay.

Analytical Essay Examples by Academic Level

Analytical Essay Examples for High School

Recommended starting points:

- Social Media Impact example (above): Clear structure, relevant topic, manageable length

- Short Gatsby example (above): Classic literature, 500 words, straightforward analysis

- Introduction examples (above): Study these for strong thesis statements

High school expectations:

- Length: 500-1,000 words (3-5 paragraphs)

- Focus: Clear thesis, basic structure, evidence with explanation

- Analysis depth: Explain what evidence shows and why it matters

- Sources: Usually 1-3 sources, may include textbook or assigned readings

Analytical Essay Example College

Recommended starting points:

- Climate Policy example (above): Multiple sources, complex argument, evaluative stance

- Critical Analysis example (above): Methodological evaluation, research synthesis

- Article Analysis example (above): Argument evaluation, logical analysis

College expectations:

- Length: 1,000-2,000 words (5-8 paragraphs)

- Focus: Sophisticated thesis, complex argumentation, multiple perspectives

- Analysis depth: Explain mechanisms, evaluate implications, synthesize sources

- Sources: 4-8+ sources, scholarly research expected

Key difference: High school analysis often asks "what does this mean?" while college analysis asks "how does this work, why does it matter, and what are the limitations?"

Download Analytical Essay Examples (PDF)

Want to study these offline? Download our example essays as PDFs.

Ready for One With Your Name on It?

Our writers deliver polished analytical essays: researched, structured, and ready to submit.

- Confidential & secure service

- 100% human-written

- Delivered on time, every time

- Unlimited revisions

Same quality. Your topic. Your deadline.

Order NowBottom Line

The best way to write a great analytical essay is to study great analytical essays. Use these examples as models: steal the structure, adapt the techniques, make it your own. Notice how strong thesis statements make arguable claims, how body paragraphs balance evidence with analysis, and how examples connect individual points to larger arguments. Study the patterns, practice the skills, and you'll develop your own analytical voice. And if you need backup, you know where to find us.