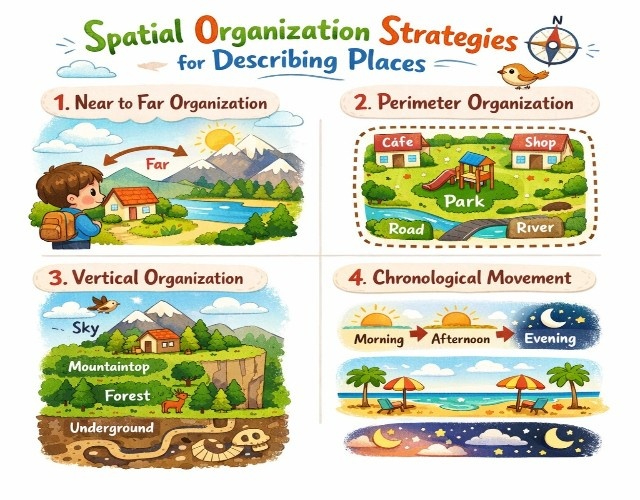

Spatial Organization Strategies for Describing Places

Places exist in physical space, which means you need a pattern for moving through them. Random jumping from detail to detail disorients readers. You need a clear path through the space that readers can follow.

1. Near to Far Organization

Start with what's closest and move outward. This works well for places where you have a fixed viewpoint, like describing a landscape from a specific spot or a room from the doorway.

Example: You're standing in a bedroom doorway. First, describe the threshold itself (the scuffed wood, the loose hinge). Then the items near the door (shoes piled against the wall, a coat hook). Then the middle space (bed, desk, window). Finally, the far wall and what you see through the window beyond.

This pattern feels natural because it's how we actually see when we enter a space.

2. Perimeter Organization

Move around the edges of a space in a circle. Start at one point and travel clockwise or counterclockwise, describing what you encounter along the walls or boundaries.

This works especially well for rooms, courtyards, city blocks, or any enclosed space where the boundaries matter more than the center.

Example: Start at the north wall of a classroom. Describe the bulletin board, the posters, and the water stain near the ceiling. Move to the east wall with its three windows and the radiator beneath them. Continue to the south wall (whiteboard, clock, teacher's desk). Finish with the west wall (door, supply cabinet, light switches).

Readers can mentally map the space as you describe it.

3. Vertical Organization

Move from ground to sky or floor to ceiling. This works for tall spaces, multi-story buildings, forests, mountains, or anywhere height matters to the character of the place.

Example: A cathedral. Start with the stone floor (worn smooth in paths where centuries of feet have walked, cracked near the entrance where water seeps in). Move to eye level (wooden pews, carved saints on pillars, the smell of incense and old wood). Then upward (ribbed vaulting, stained glass windows, the ceiling lost in shadow).

The progression creates a sense of scale and helps readers feel the vertical space.

4. Chronological Movement

Describe the place as you move through it over time. This works when the experience of moving matters as much as the destination. Walking through a city, hiking a trail, driving through a neighborhood.

Example: A walk through a neighborhood at dawn. First block: houses still dark, one porch light left on, sprinklers starting their cycles. Second block: coffee shop opening (you smell it before you see it), someone putting out sandwich boards. Third block: school crossing guard taking position, buses beginning their routes. The place changes as you move through both space and time.

For detailed spatial organization templates and examples, see our descriptive essay outline guide.

Different Types of Places and Their Unique Requirements

Different places require different descriptive approaches. A beach demands different attention than a bedroom. A subway station creates different challenges than a forest trail.

1. Natural Outdoor Places

Beaches, mountains, forests, parks, hiking trails share certain qualities. They change with seasons, weather, and time of day. Natural sounds dominate (wind, water, wildlife, rustling leaves). Light behaves differently depending on canopy, exposure, and time of year. The challenge with natural places is avoiding clichés. Everyone knows sunsets are beautiful and beaches are sandy. You need the specific sunset (how it looked that particular evening, what it illuminated, what it left in shadow) and the specific beach (was it rocky or smooth, what did you find in the tideline, what did the sand feel like between your toes). Focus on a specific time and condition. Dawn in the forest when frost still clings to spiderwebs. The mountain trail during a sudden afternoon thunderstorm. The park in winter when ice coats every branch. Specificity defeats clichés. |

2. Built/Architectural Places

Buildings, rooms, houses, stadiums, churches, and bridges have human-made qualities. Materials matter (wood, stone, concrete, glass, metal). Acoustics change how sound behaves. Spatial layout affects how people move and gather. The challenge is making familiar spaces interesting. Everyone has been in a classroom or a bedroom. Why is this particular classroom worth describing? What specific details make this bedroom different from every other? Focus on unique details that reveal character. The crack in the ceiling tile looks like a coastline. The squeaky floorboard near the bathroom. The way light comes through the blinds in the afternoon makes stripes across the wall. The particular smell of old carpet and chalk dust. These details anchor the description in something real and observable rather than generic. |

3. Urban/City Places

Streets, squares, neighborhoods, and public spaces pulse with human activity. Noise layers upon noise. Density creates energy. Movement happens constantly. The challenge is organizing overwhelming sensory input. A city street corner hits you with hundreds of details simultaneously. You can't describe them all without exhausting readers. Two strategies work well: Select micro scenes (the hot dog vendor's cart, one conversation from passing pedestrians, the window display in a single shop) or follow one path through the space (walk one block, describing only what you encounter directly in your path). This gives readers something to hold onto rather than drowning in stimulus. |

4. Interior/Private Places

Bedrooms, offices, personal spaces, cars, and vehicles contain intimate details. Personal objects reveal character. Atmosphere often matters more than physical description. The challenge is balancing personal meaning with reader engagement. Your childhood bedroom matters to you because of memories and associations. Readers don't share those memories. You need to show why the space matters through specific objects and details that carry meaning visually. Focus on objects that tell stories. The stack of books on the nightstand (which books? Are they worn from rereading?). The photos on the bulletin board (who's in them? Are they fading?). The coffee mug stain on the desk (how old? what shape?). These details let readers understand the significance without you explicitly stating it. |

Need place topic ideas? Browse 250+ descriptive essay topics, including natural environments, urban spaces, historic buildings, personal locations, and travel destinations, organized by category.

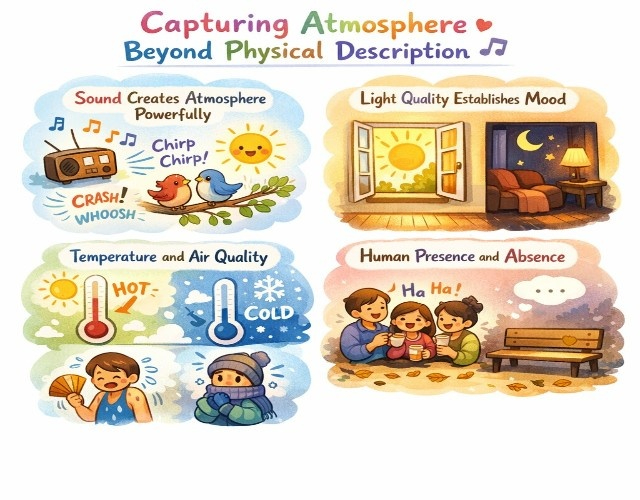

Capturing Atmosphere Beyond Physical Description

Physical details establish place, but atmosphere makes it memorable. Two writers can describe the same room with identical physical details and create completely different feelings based on how they handle atmosphere.

1. Sound Creates Atmosphere Powerfully

Sound tells you about life in a place. The distant hum of traffic says you're in a city. Complete silence except for the wind in trees says something else entirely. The rhythmic thump of bass from an upstairs apartment says neighbors live close.

Layer multiple sounds when relevant

| A subway station: The screech of brakes, the robotic announcement voice, dozens of conversations blending into white noise, footsteps echoing on tile, someone's headphones leaking music, a busker's saxophone in the distance. Each sound adds to the total atmosphere. |

But sometimes one sound dominates and defines the space. A hospital room where the only sound is the ventilator's steady rhythm. A library where the silence feels physical. These focused moments work because the sound (or lack of it) becomes the atmosphere itself.

2. Light Quality Establishes Mood

Light changes everything about how a place feels. Harsh fluorescent office lighting creates a different atmosphere than afternoon sun through sheer curtains. Dawn light differs from twilight even when illuminating the same scene.

Describe what light does rather than just noting its presence

| Light doesn't just exist in a room. It pools on the floor beneath the window. It catches dust floating in the air. It makes one side of a person's face bright and leaves the other in shadow. It turns white walls golden or blue depending on the time of day. |

Time of day matters for mood

| Morning light feels hopeful. Late afternoon light feels melancholy. Midnight lighting (streetlamps, neon signs, the blue glow from windows) creates isolation even in crowded spaces. |

3. Temperature and Air Quality

Temperature affects how people experience a place. The specific humidity of a subway platform in August. The dry cold of a mountain morning. The stuffy warmth of an overheated classroom in winter. These physical sensations ground readers in the space.

Air quality tells you about a place, too. Does it smell like fresh rain or car exhaust? Pine needles or garbage? Coffee brewing or disinfectant? Bread baking or industrial chemicals? Smell triggers memory and emotion more powerfully than any other sense.

Sometimes the air itself has qualities beyond temperature and smell. Thickness (humidity that makes breathing feel like work). Thinness (high altitude, where you notice every breath). Stillness (no breeze, air sitting heavy). Movement (wind constant enough to be a presence).

Bring Your Favorite Place to Life in Words

Get expert help creating vivid, sensory rich place descriptions

Our essay writing service helps you turn meaningful places into compelling, high scoring essays.

4. Human Presence and Absence

Places feel different when people occupy them versus when they sit empty. A playground during recess versus the same playground at midnight. A stadium during a game versus the empty stadium the next morning.

Describe traces people leave

| The warm spot on a bench where someone just sat. Coffee cups left on tables. The indent in the carpet where furniture used to be. Graffiti on walls. These signs of human presence create an atmosphere even when no one's currently there. |

When people are present, describe how they interact with the place. Do they move quickly or linger? Do they speak loudly or whisper? Do they gather in groups or stay separate? The relationship between people and place reveals both.

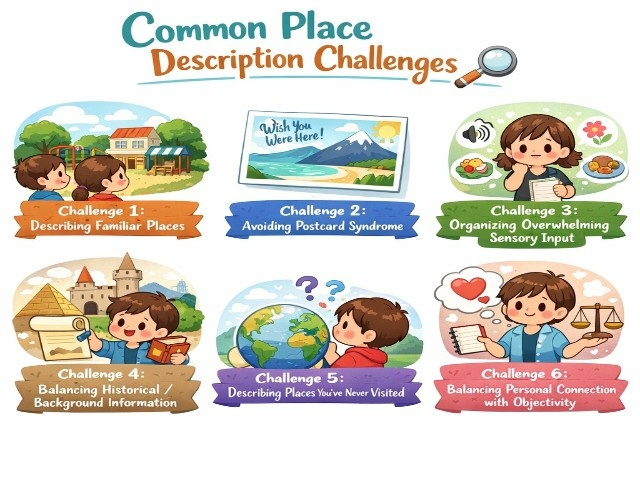

Common Place Description Challenges

Certain challenges come up repeatedly when describing places. Recognizing them helps you avoid common mistakes.

Challenge 1: Describing Familiar Places

Places you see every day become invisible. Your own bedroom, your route to school, your favorite coffee shop stop being noticed because familiarity breeds blindness.

The solution is forced re-observation. Visit the place as if for the first time. Bring a notebook. Spend ten minutes doing nothing but noticing details you've stopped seeing. The stain on the ceiling you forgot about. The sound the door makes when it closes. The particular smell when you first walk in.

Pretend you're explaining this place to someone who's never seen anything like it. What would they need to know to picture it accurately?

Challenge 2: Avoiding Postcard Syndrome

"The beach was beautiful. The sunset was gorgeous. The mountains were majestic." This tells readers nothing because these are conclusions rather than observations.

What made the beach beautiful? The specific way tide pools reflected the sky. The texture of sand (coarse or fine, wet or dry). The particular color of water (gray-green, turquoise, brown with stirred sediment).

Replace every abstract judgment (beautiful, peaceful, scary, cozy) with the concrete details that created that judgment. Don't say the room felt cozy. Describe the soft throw blanket on the couch, the warm light from table lamps, and the faint smell of vanilla candles. Let readers conclude "cozy" from the evidence.

Challenge 3: Organizing Overwhelming Sensory Input

Complex places (busy city streets, crowded markets, festivals, large public spaces) bombard you with more details than you can possibly describe. Trying to capture everything results in chaotic lists.

Choose one organizational principle and stick to it. Follow one path through the space. Focus on one sense at a time and layer them. Select representative details rather than comprehensive inventories.

The goal isn't documenting every detail. It's selecting the details that best convey the character and atmosphere of the place. Five specific, vivid details beat twenty generic ones.

Challenge 4: Balancing Historical/Background Information

Some places (historic buildings, famous landmarks, culturally significant sites) carry context beyond their physical reality. You want readers to understand why the place matters without turning your description into a history lesson.

Weave context into physical description. Don't stop describing to explain history. Instead, let historical details emerge through observation.

Example: Don't say "The theater was built in 1923 during the silent film era and featured elaborate Art Deco ornamentation typical of movie palaces." Instead: "The theater's gilt ornamentation caught light from the original 1923 fixtures, and the curved walls (designed for acoustics before sound systems existed) still showed traces of their original Art Deco murals beneath decades of paint."

The historical information is there, but it's embedded in the description rather than interrupting it.

Challenge 5: Describing Places You've Never Visited

Sometimes you need to describe a place you haven't personally observed, historical locations, places from research or photographs, or imaginary places based on real locations.

The challenge is missing sensory details. Photos show you sight but not sound, smell, temperature, air quality, or the feel of surfaces. Videos add sound but flatten scale and spatial relationships.

Be honest about limitations when necessary. If you're describing a historical place based on research, you can acknowledge this while still being specific. "Contemporary accounts describe..." "Photographs show..." "According to records..."

Focus on research-based details you can verify. Architectural measurements, documented materials, and recorded observations from the time period. These give you concrete details even without firsthand observation.

When writing fiction or imagining places, research analogous real places. If you're describing an imaginary Victorian mansion, study real Victorian mansions through photos, floor plans, and architectural guides. Real details make imaginary places convincing.

Challenge 6: Balancing Personal Connection with Objectivity

Places often matter personally, your childhood home, your grandmother's kitchen, the park where something important happened. The emotional connection is real and can strengthen description, but uncontrolled sentimentality weakens it.

The risk is over-sentimentalizing (everything becomes precious and important) or becoming so detached that description feels clinical and cold.

Ground emotions in physical details. Don't say "The kitchen smelled like my grandmother's cooking, and it made me nostalgic." Instead, specify what dishes, when, and why the smell mattered. "The kitchen still smelled faintly of cardamom from yesterday's tea, and that smell meant my grandmother's afternoon routine, the careful heating of milk, the precise ratio of spices she'd measured the same way for forty years."

Let emotion guide your detail selection, but describe concrete, observable reality. The emotion will come through without you stating it directly.

Writing Your Own Place Description

The process of writing place descriptions benefits from a systematic approach. These steps help you move from raw observation to polished prose.

Step 1: Experience the Place with a Notebook

Return to the location if possible. If you're working from memory, spend focused time recalling it in detail. Don't trust your general memory, it's selective and unreliable.

List everything you remember across all senses

|

Also note

|

Need place ideas to get started? See our complete list of descriptive essay topics for inspiration.

Step 2: Choose Your Spatial Organization Pattern

Review the four patterns (near-to-far, perimeter, vertical, chronological) and select one based on

|

Sketch a simple map or diagram showing the pattern you'll follow. This doesn't need to be detailed, just enough to keep you organized while writing.

Step 3: Layer Your Sensory Observations

Don't separate description into "sight paragraph, then sound paragraph, then smell paragraph." That feels artificial. Instead, layer multiple senses together as you move through the spatial pattern.

| Example (using near to far in a bedroom): "The doorway threshold is scarred wood, grooves worn by decades of shoes. Just inside, shoes pile against the wall, sneakers, boots, heels tangled together, carrying the faint smell of worn leather and street salt. The bed dominates the middle space, unmade, sheets twisted from restless sleep, still holding the warmth from earlier. Beyond it, the window shows weak winter light, and cold air seeps through the old frame, making the room feel divided into warm center and cold perimeter." |

This description moves spatially from the door to the shoes, then to the bed, and finally to the window, while incorporating sight, smell, temperature, and touch.

Step 4: Identify Your Dominant Impression

What's the one feeling or quality you want readers to take away? Peaceful, chaotic, oppressive, welcoming, abandoned, lived-in, pristine, decaying?

Every detail you include should reinforce this impression. Cut details that contradict it, even if they're accurate.

If your dominant impression is "abandoned," emphasize dust, silence, disrepair, emptiness, faded colors, broken objects, and things left behind. De-emphasize or eliminate details that suggest recent habitation or active maintenance.

Consistency creates a powerful atmosphere. Mixed signals create confusion.

Step 5: Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

Start with your dominant impression stated as a clear sentence. "The house had been empty for years, and it showed." Then begin your spatial organization pattern.

End by returning to that dominant impression, but deepened by everything you've shown. "The house had been empty for years. But empty isn't the same as lifeless. It was waiting."

The circular structure gives readers a complete experience. They know where they're going from the start, they take the journey through the description, and they arrive at a deepened understanding of where they've been.

Place Description Examples by Type

These examples show different approaches for different types of places. Notice how each uses specific details to create atmosphere while maintaining clear spatial organization.

Natural Landscape: "The Trail at Dawn"

The trail starts where gravel meets forest floor, a gradual transition from maintained path to wild ground. You notice it in your feet first. The solid crunch of stone giving way to the softer give of earth and pine needles. Roots cross the path every few yards, worn smooth by thousands of boots but still substantial enough to watch for.

The forest smells different at dawn than at midday. Cooler. The scent is more distinct: damp earth, decomposing leaves, the sharp green smell of ferns. Nothing has heated up and mixed yet. Each smell stays separate.

Light comes through the canopy in shafts rather than general illumination. You walk through alternating bands of cool shadow and surprising warmth where the sun reaches the forest floor. The contrast is physical. In shadow, you feel the night's lingering cold in the air. In the sunlit patches, your shoulders warm within seconds.

Sound tells you about wildlife you can't see. A bird you don't recognize is calling from deeper in the trees. Something small is moving through underbrush twenty feet to your left. The creek, before you see it, is a low, steady rush that gets louder as you walk. When you finally reach it, the sound isn't louder so much as more textured. You can distinguish individual splashes, the different pitch of water over rocks versus water in deeper pools.

The air tastes clean in a way that makes you aware of every breath.

Urban Space: "The Subway Platform, 6 PM"

The platform is narrower than it looks from the top of the stairs. Once you're down and the crowd fills in behind you, personal space becomes theoretical. You stand where there's room, shoulder to shoulder with strangers who've perfected the art of not making eye contact.

The air is wrong, too warm for the season, thick with mechanical smell and human density. Not quite body odor, but the smell of bodies existing in proximity. Deodorant and coffee breath and someone's perfume fighting a losing battle against the institutional smell of underground concrete and brake dust.

A train arrives across the platform. The sound builds from a distant rumble to a shriek of brakes to the pneumatic hiss of doors opening. The automated voice announces something, but the acoustics turn it into garbled echoes. No one needs to hear it anyway. Everyone knows when their train comes.

Your train isn't this one, so you wait. A busker sets up near the tunnel entrance, saxophone, weathered case open for change, a determination in how he stands that says this is his corner and he's earned it. He starts playing something that might be jazz. The sound bounces off tile walls, multiplies, and becomes bigger than one saxophone should be able to produce.

People around you shift and resettle like water finding its level. Making microscopic room when someone squeezes past. Filling gaps when someone leaves. The platform never empties. People flow in and out, but the density stays constant during rush hour.

Somewhere down the tunnel, you feel more than hear the rumble that means your train is coming.

Interior Space: "The Diner at Midnight"

The booth vinyl is cracked in a pattern that suggests decades rather than neglect. The kind of worn that comes from people sliding in and out tens of thousands of times. It's cold against your legs for the first few seconds, then body-temperature warm.

The menu doesn't need reading; you know what diners serve at midnight, and this one is no exception, but you pick it up anyway because it's part of the ritual. The plastic coating is slightly sticky. Someone wiped it down, but not recently enough.

Behind the counter, the grill is audible proof that someone's still cooking. The sizzle of something hitting hot metal. The scrape of a spatula. The cook works without looking at his hands, that particular competence of someone who's made the same motions for years.

The fluorescent lights give everything a quality that's somewhere between harsh and clinical. Nothing is shadowed. Nothing is flattering. The lights show every watermark on the ceiling tiles, every scuff on the floor, every age line on the waitress's face when she comes over with coffee already poured.

She fills your cup without asking if you want it. That's not rudeness. That's understanding diner protocol. Nobody sits at a diner at midnight without wanting coffee.

Two other customers: a man reading a newspaper at the counter, the paper itself an anachronism, and someone in the corner booth who might be asleep or might just have their head down. The jukebox in the corner is dark and silent. Nobody plays music after 11 anymore. Nobody fed it quarters.

Outside the window, the street is wet from rain you didn't hear start. Headlights slide past, turning puddles into brief mirrors.

Historic Building: "The Abandoned Theater"

The lobby still shows traces of its original grandeur, if you know where to look. The floor's checkerboard tiles (black and white marble, now thick with dust and water damage) suggest what money built this place. Art Deco patterns run up the walls in gold leaf that's mostly flaked away but catches light in unexpected places.

The chandelier hangs at an angle. Several feet of chain are visible where it's pulled away from the ceiling. Crystal pendants are missing in a pattern that suggests they fell rather than were stolen; a scattering of glass on the floor beneath confirms it.

You can hear the building settling. Creaks and groans that might be thermal expansion or might be slow structural failure. Water drips somewhere deeper in the building, a steady rhythm that echoes through empty spaces. The acoustics are still good. The theater was designed to carry sound, and that design works even in decay.

The air smells like old carpet, water damage, and pigeon droppings. Something organic is breaking down. Not quite rot, but heading that direction. Cold, too, the heating died years ago, and these old buildings don't hold warmth without active systems running.

Through the doors to the theater proper, the seats remain in rows. Most are still intact. Red velvet faded to something closer to brown. Some have collapsed springs. Some are missing sections of upholstery where decay or theft has taken pieces. But they face the stage as they have since 1928, waiting for a performance that isn't coming.

The screen is torn, a diagonal slash from upper left to lower right, edges curling. Behind it, the stage is visible. Smaller than you'd expect. The proscenium arch looms large, but the actual performance space is intimate.

Graffiti covers parts of the walls. Not artistic murals but territorial markers and crude drawings. The building's decline was documented in spray paint.

Outdoor Recreation Space: "The Basketball Court, 6 PM"

The court surface is cracked concrete, not the smooth kind from professional gyms but the outdoor variety with aggregate showing through where the top layer has worn away. Your shoes make different sounds depending on where you step, solid thwack on intact areas, different pitch over cracks, almost nothing on the parts where weeds push through.

The hoops are chain nets. Not the satisfying swish of nylon but a metallic rattle-and-clang when someone scores. The sound carries across the court and tells everyone within earshot that someone made a shot. The backboards are metal too, which means bank shots sound harder and uglier than they should. No give, just impact.

The light is changing, that specific quality of early evening when the sun's still up but low enough that shadows stretch long across the court. Half the court is still in direct light, bright enough to squint. The other half is in shadow from the apartment building next door. Players adjust their game around this. You don't take three-pointers from the shadowed side if you can avoid it. The depth perception is wrong.

Sound layers: the ball bouncing (that rhythmic thud-thud-thud that sets tempo for everything else), shoes squeaking when someone cuts hard, heavy breathing from players who've been at it for the last hour, the occasional clash of elbows and bodies that aren't quite fouls but aren't quite clean either. And talking, constant talking. Trash talk, encouragement, calling plays, calling fouls, and arguing calls.

The air smells like hot concrete and sweat and someone's body spray applied too heavily. The temperature is still oppressive, heat radiating off the concrete even though the day is cooling. By full dark, the court will be comfortable. Right now, you're playing through the worst of it.

Six guys on the court, another four waiting on the sideline. Game to eleven, winner stays. The waiting players watch with the focus of people planning how they'll attack when it's their turn. Everyone knows everyone else's game. You've all been playing on this court for months or years. You know who shoots lefty, who can't go left, who plays too physical, who calls ticky-tack fouls.

A pickup game has rhythm and unspoken rules that outsiders wouldn't recognize, but insiders navigate automatically. This is structured chaos with tribal knowledge.

Personal/Private Space: "My Childhood Bedroom, Revisited"

The room is smaller than the memory preserved in it. Not by a little, by half. The ceiling that seemed impossibly high is barely seven feet. The closet I played in as a fortress is a shallow alcove I can't fully stand in.

My parents left it largely untouched, which means it's a time capsule I don't entirely remember creating. Posters on the wall: bands I couldn't name now, movies I barely recall watching. A pennant from a sports team I never actually followed but somehow acquired. The bulletin board still displays ribbons from elementary school events that seemed monumental at age nine.

The bookshelf shows archaeology. Bottom shelf: picture books I learned to read with, spines cracked from repetition. Second shelf: chapter books from middle school, many with library stamps because I borrowed before buying. Third shelf: high school texts, some with highlighting, some clearly unread. Top shelf: aspirational books I claimed to have read but never opened.

The bed is the same. The quilt my grandmother made still covers it, faded now, one corner where the stitching's coming loose. It smells like the house generally (my parents' laundry detergent, the specific scent of this building's climate), not like me at age sixteen. Whatever smell I contributed has been laundered and aired away.

Dust hangs visible in the afternoon light through the window. The window that once provided an escape route and an adventure point now just shows the neighbor's garage. The view hasn't changed. My perception of it has.

The closet still contains clothes that don't fit, not just size, but style and identity. T-shirts from concerts I attended, hoodies from schools and camps, and formal shirts from events I needed them for. Artifacts of former selves I'm not sure I recognize.

What strikes me most is the silence. This room was loud with music and friends, and teenage energy. Now it's museum quiet, waiting for nothing in particular.

| For more descriptive essay examples across different topics and approaches, see our complete descriptive essay examples collection. |

Key Takeaways

Effective place descriptions combine systematic spatial organization with layered sensory details and consistent atmosphere. Choose one pattern for moving through space and stick with it. Layer multiple senses together rather than separating them artificially. Ground every observation in concrete, specific details rather than abstract judgments. Let your dominant impression guide detail selection. Balance objective observation with the emotional resonance that makes places matter.

The goal is to immerse readers so fully in the place that they feel like they’re experiencing it firsthand, not just reading about it. For broader techniques and structure, refer to our descriptive essay guide.

Turn Your Place Description into a Memorable Essay

Professional support for writing detailed and engaging descriptive essays

- Capture atmosphere, emotions, and unique details effectively

- Learn how to structure place based descriptions properly

- Avoid common descriptive essay mistakes

- Receive expert reviewed, polished academic writing

With our essay writing service, you can confidently submit descriptive essays that leave a lasting impression.

Order Now-20188.jpg)

-20161.jpg)

-20358.jpg)

-20173.jpg)