Understanding Self Description

A descriptive essay about myself is a piece of writing where you describe your personality, experiences, values, or characteristics using sensory details and vivid language. It's different from a narrative essay (which tells a story) or an expository essay (which explains something). Instead, you're creating a snapshot of yourself that helps readers see, feel, and understand who you are.

This type of essay is common in college applications, scholarship essays, and creative writing classes. You might need to describe your background, your passions, your goals, or what makes you unique. The key is showing rather than telling, using concrete details instead of vague statements.

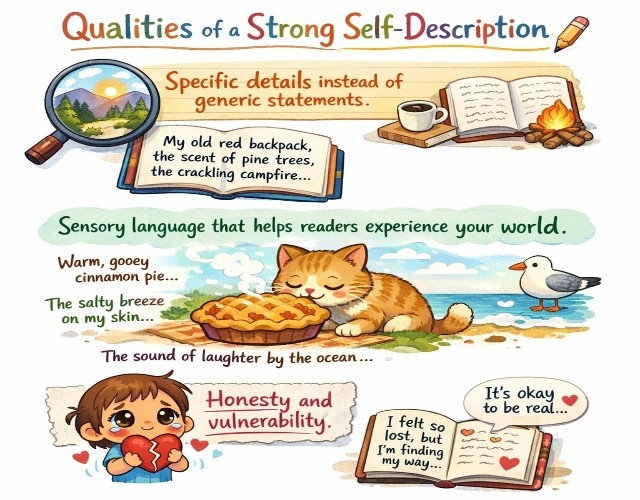

Qualities of a Strong Self Description

Let's get practical. A good descriptive essay about yourself has three essential elements:

Specific details instead of generic statements. Don't say "I'm hardworking." Show yourself studying at 2 AM with cold coffee and highlighters scattered across your desk. Don't say "I love my family." Describe your grandmother's laugh or the smell of your dad's famous Saturday pancakes.

Sensory language that helps readers experience your world. Use sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. Instead of "I was nervous," try "My hands trembled as I gripped the microphone, and I could taste the metallic tang of adrenaline on my tongue."

Honesty and vulnerability. The best essays about yourself don't pretend you're perfect. They acknowledge your quirks, your failures, and your growth. Admissions officers and readers can spot fake authenticity from a mile away. Real flaws make you relatable. Perfect people are boring.

Think about it this way: if someone read your essay without seeing your name, would they recognize you? Would your friends say "yep, that's definitely [your name]"? If not, you're probably being too generic.

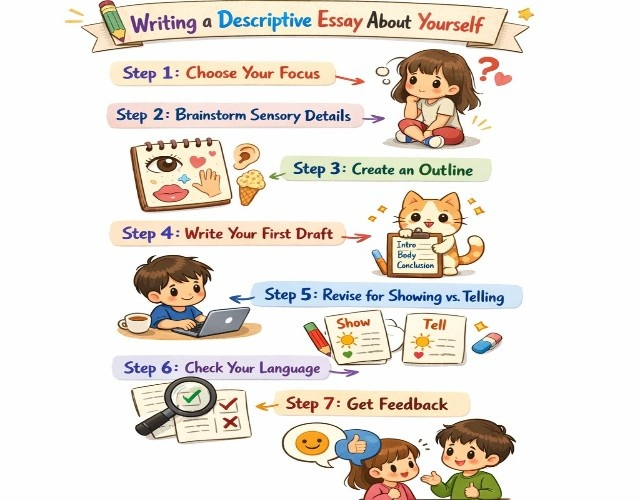

Step by Step Guide to Writing a Descriptive Essay About Yourself

Let's break down the writing process into manageable steps.

Step 1: Choose Your Focus

You can't describe everything about yourself in one essay. Pick one angle. Ask yourself:

- What makes me different from others?

- What experience shaped who I am?

- What trait do I want others to understand about me?

- What story from my life best captures my personality?

Write down three possible topics. Then pick the one that excites you most or that you have the most specific details about.

Step 2: Brainstorm Sensory Details

Once you've chosen your focus, brainstorm sensory details. Close your eyes and remember:

- What did you see? (Colors, shapes, facial expressions, settings)

- What did you hear? (Voices, music, background noise, silence)

- What did you smell? (Food, perfume, rain, old books)

- What did you taste? (If relevant)

- What did you feel physically? (Temperature, texture, pain, comfort)

- What did you feel emotionally? (Don't just name the emotion, describe how your body felt)

Write these down in a list. Don't organize yet, just capture everything you remember.

Step 3: Create a Structural Framework

A basic structure for a descriptive essay about yourself includes three main parts: introduction, body, and conclusion.

Start with an engaging hook, briefly provide context, and present a clear thesis that highlights the main idea about yourself without directly announcing it. In the body paragraphs, focus on two to three key aspects of your personality or experiences, using specific examples and sensory details to support each point.

You may also include a brief reflection to add depth. Conclude by summarizing your main ideas in a fresh way, then end with a meaningful reflection that leaves a lasting impression.

If you need to learn more about the organizing tips and structure, visit our descriptive essay outline guide.

Step 4: Write Your First Draft

Don't edit while you write your first draft. Just get words on the page. Follow your outline loosely but allow yourself to discover new ideas as you write.

Start with the body paragraphs if your introduction feels intimidating. Many writers find it easier to write the intro last, once they know what they're actually introducing.

Use specific nouns and strong verbs instead of adjectives and adverbs. Instead of "walked quickly," say "rushed" or "sprinted." Instead of "very happy," say "ecstatic" or "overjoyed."

Step 5: Revise for Showing vs. Telling

This is where most self-description essays fail. Students tell instead of show.

See the difference? The second version lets readers conclude you're determined. You don't have to announce it. |

Go through your draft and circle every adjective you used to describe yourself. Then replace each one with a specific example or sensory detail that demonstrates that trait.

Step 6: Check Your Language

Read your essay out loud. Does it sound like you? Or does it sound like you're trying too hard to impress someone?

Look for

|

Your essay should sound polished but not fake. Think "your best self having a meaningful conversation," not "robot reading from a script."

Step 7: Get Feedback

Ask someone who knows you well to read your essay. Do they recognize you in it? Does it capture your personality? Are there details they think you should add or remove?

Also ask them:

|

Be open to criticism. You're too close to your own writing to see it objectively.

Get Expert Writing Assistance Today

Professional writers ready to help you craft a compelling descriptive essay about yourself.

Don't let writer's block stop you from showcasing who you are.

Finding Your Authentic Voice for Self Description Essay

An authentic voice makes a self description memorable and engaging. It reflects your natural word choice, sentence flow, personality, and unique perspective. Instead of trying to sound overly academic or impressive, write in a way that feels genuine to you. Your distinct experiences, observations, and viewpoints help readers connect with your story.

You don’t need to explain everything; focus on meaningful details and trust readers to understand your perspective. If humor comes naturally, it can strengthen your voice and show self-awareness, but sincerity is equally powerful. A genuine, personal tone is what makes your self-description stand out.

Choosing What to Reveal About Yourself

Strategic revelation balances interesting details with appropriate boundaries. Not every personal fact belongs in every essay.

High value revelations include:

- Moments that changed your perspective or behavior.

- Unexpected interests or talents that complicate stereotypes.

- Vulnerabilities that demonstrate growth or self-awareness.

- Specific scenes revealing character through action.

- Contradictions that show complexity rather than confusion.

Low value revelations include:

- Generic qualities everyone claims ("I'm a people person").

- Oversharing inappropriate personal information.

- Random facts unconnected to your essay's focus.

- Complaints without reflection or growth.

- Humble-brags disguised as modesty.

The "so what?" test helps determine value: If you reveal something about yourself, ask "so what?" Does this detail help readers understand something meaningful? Does it connect to your essay's larger point? If the detail simply exists without significance, cut it regardless of how interesting you find it personally.

Vulnerability, handled skillfully, creates a powerful connection. Revealing struggles, failures, or insecurities, when paired with reflection on what you learned, demonstrates maturity and emotional intelligence. However, vulnerability requires boundaries. You're writing an essay, not therapy notes.

| For frameworks organizing self revelations effectively, study our descriptive essay outline guide with templates for personal essays. |

Common Mistakes to Avoid in a Self Descriptive Essay

| Mistake | Why It’s a Problem | Better Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Being Too Modest | Downplaying your strengths prevents readers from understanding your true abilities. | Honestly, highlight your strengths with specific examples and evidence. |

| Being Too Arrogant | Overconfidence can make you seem unlikable or unrealistic. | Balance confidence with humility and acknowledge growth and challenges. |

| Using Clichés | Overused phrases sound generic and fail to show your unique personality. | Use original language and personal experiences to express your ideas. |

| Listing Accomplishments | A resume style list doesn’t reveal who you are as a person. | Show your qualities through stories and meaningful experiences. |

| Forgetting Your Audience | Irrelevant tone or content may fail to connect with readers. | Adjust your tone and details based on who will read your essay. |

| Ignoring Word Count | Not following limits shows lack of attention to instructions. | Stay within the required word count and focus on quality content. |

Examples of Effective Self Description

Example 1: "The Chameleon" (Contrast Pattern)

At debate tournaments, I'm precise and aggressive, interrupting opponents mid-sentence, speaking rapid-fire, never conceding a single point. My rebuttals come loaded with statistics and citations, delivered in a tone that suggests anyone disagreeing must be either uninformed or deliberately obtuse. I've won trophies for this strategic ruthlessness.

But in my grandmother's kitchen, I'm someone entirely different. There, I move slowly, listening more than speaking. I ask questions about recipes passed through generations, about my grandfather who died before I was born, about how things were different "back then." I measure ingredients she estimates by feel, trying to preserve traditions I fear might disappear. In that kitchen, I never interrupt, never challenge, never need to win anything except her smile when I finally nail the dough consistency.

These versions of me, the debater and the granddaughter, seem contradictory until I realize they're both authentic. Both emerge from the same core: I care intensely. In debate, I care about truth and arguments and intellectual honesty. In the kitchen, I care about connection and heritage and preserving what matters before it's lost. I've stopped trying to reconcile these selves into one consistent personality. Maybe being multifaceted isn't confusion; it's just being human.

What Works: Establishes contrast immediately, uses specific details (interrupting opponents, measuring by feel), avoids resolving contradiction artificially, and demonstrates self-awareness through reflection.

Example 2: "The Afternoon I Quit" (Defining Moment Pattern)

I'd played piano for eleven years when I walked into Mr. Chen's studio and announced I was quitting. Not taking a break. Not reducing practice hours. Quitting entirely, immediately, and permanently.

He didn't seem surprised. He'd probably seen this coming through the progressively shorter practice logs I'd submitted, the mistakes I'd stopped bothering to correct, the recital pieces I'd learned just barely well enough to perform before forgetting them completely.

"Why now?" he asked, which was kinder than asking why I'd wasted eleven years.

I'd been trying to articulate this for months. "Because I'm good at it, but I don't love it. My parents love that I play. My college applications love that I've played for eleven years. But I've realized I'm building a life around obligations I never chose, and if I don't stop now, I'll wake up at thirty doing a job I tolerated because it looked impressive, married to someone I dated. After all, it made sense, living in a place I never actually picked."

Mr. Chen nodded slowly. Then he played a piece I'd never heard, full of mistakes and hesitations but also joy. "This is what I sound like when I play for myself," he said. "Not for recitals or students or anyone's expectations. This is how I know I still love it."

I didn't change my mind. But I understood his point. I needed to find my version of that, something I'd do even if nobody was watching, grading, or approving. Six months later, I started rock climbing. I'm terrible at it. I probably always will be. But three nights a week, I'm at the gym, chalk-dusted and exhausted and completely certain I'm exactly where I should be.

What Works: Focuses on a single pivotal decision, includes dialogue for authenticity, balances external action with internal reflection, concludes with growth rather than resolution, and reveals character through choices.

Free Downloadable Resources for a Descriptive Essay About Myself

| Want to see more examples? Explore our collection of descriptive essay examples for additional inspiration. |

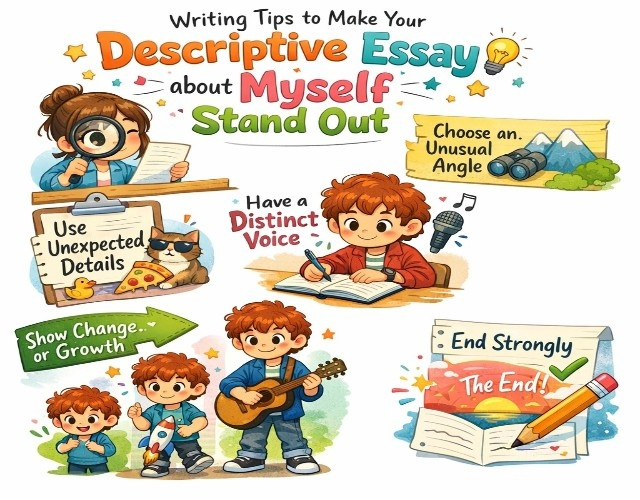

Writing Tips To Make Your Descriptive Essay about Myself Stand Out

Everyone writes about their challenges, their passions, their backgrounds. How do you make yours memorable?

1. Choose an Unusual Angle

Instead of writing about how you overcame a challenge (which everyone does), write about a challenge you failed at and what you learned. Instead of your biggest achievement, write about your most ridiculous mistake.

2. Use Unexpected Details

The small, weird, specific details are what make essays memorable. Don't just say you love your grandmother. Mention how she always has exactly three butterscotch candies in her purse, and you can't remember a time when that wasn't true.

3. Have a Distinct Voice

Your writing voice should sound like you. If you're naturally funny, let that come through. If you're serious and thoughtful, embrace that. Don't try to sound like someone you're not.

4. Show Change or Growth

The most compelling essays show transformation. You don't have to be a completely different person, but showing how you've changed, learned, or evolved makes the essay more dynamic.

5. End Strongly

Your conclusion should leave readers thinking. It shouldn't just repeat what you already said. Instead, zoom out. What does this characteristic or experience mean in the bigger picture? What will you do with this understanding of yourself?

Describing Different Aspects of Yourself

1. Physical Appearance

If you need to include a physical description, make it meaningful. Don't just list features. Connect your appearance to experiences or identity.

- Instead of: "I have brown hair and green eyes."

- Try: "My red hair came from my Irish grandmother, along with her temper and her stubborn refusal to let anyone tell her what to do."

2. Personality Traits

Again, show don't tell. Every personality trait should be demonstrated through specific examples, not announced.

3. Values and Beliefs

This gets tricky because you want to avoid sounding preachy. The best approach is to show your values in action rather than listing what you believe.

- Instead of: "I believe in helping others."

- Try: "Every Tuesday and Thursday, I tutor middle schoolers in math. Last week, a seventh grader finally understood fractions after months of struggling, and her smile made my entire semester worthwhile."

4. Relationships

Your relationships say a lot about who you are. How you interact with family, friends, teachers, and strangers reveals your character. But be careful, this essay is about you, not about them. Use relationships to illuminate your own qualities.

| Exploring different approaches? Read about descriptive essays about a person for related techniques. |

Different Contexts for Self Description Essays

College Application Essays

These need to show admissions officers why you'd be a valuable addition to their campus. Focus on qualities that demonstrate you'll succeed academically and contribute to the community. Length is usually 500 to 650 words. Be concise and purposeful with every sentence.

Scholarship Essays

Scholarship committees want to know you'll use their money well. Emphasize your goals, your commitment to education, and how this scholarship will help you achieve your dreams.

But don't just talk about needing money. Show your character, your work ethic, your potential.

| Want to know more? Check our scholarship essay guide. |

Creative Writing Assignments

These give you more freedom. You can be more experimental with structure, style, and content. The focus is on your writing skills as much as your self-description.

This is your chance to take risks and show creativity.

Personal Statements

For graduate school or job applications, personal statements blend self description with professional goals. You're describing yourself in the context of your career aspirations.

Be more formal here, but still authentic and specific.

Final Thoughts

Writing a descriptive essay about yourself is both easier and harder than it seems. Easier because you know the subject intimately. Harder because you have to step outside yourself enough to see what's actually interesting and worth describing.

The best self description essays are honest, specific, and vivid. They show rather than tell. They use sensory details to bring experiences to life. They reveal something meaningful about who you are without announcing "I am X type of person."

Remember that this essay is your chance to control the narrative. You get to decide what aspect of yourself to highlight, which stories to tell, and which traits to demonstrate. Make those choices purposefully.

You can also explore our descriptive essay writing guide for step by step techniques that help you shape a clear, engaging, and authentic self-portrait.

In the end, the best descriptive essays don’t just describe you, they help readers understand you.

Ready to create an outstanding descriptive essay?

Our professional writers are here to help you craft an essay that truly captures who you are.

- Tell us about your subject and descriptive requirements

- Get matched with a creative writing expert

- Receive drafts with rich sensory language

- Get your final essay with powerful descriptive techniques

Every essay is crafted with careful word choice, figurative language, and immersive descriptions that engage all five senses.

Order Now

-20161.jpg)

-20188.jpg)

-20358.jpg)

-20173.jpg)